Situational Awareness via Information Spaces: Overview

When it comes to decision making in a variety of civilian and security applications, for example search-and-rescue, pursuit-evasion, and monitoring, having the right information is of critical importance. These problems are known as

situational awareness (SA)

problems. As one can imagine, an effective cyber-physical system critically depends on its awareness of its ambient environment. A particularly important SA sub-category is target-tracking, in which (fixed and mobile) sensor observations are processed to provide the best possible estimate of one or more mobile targets. Because mobile targets will inevitably fall out of the

field-of-view (FOV)

of the sensors (see the figure on the left), consistent information can be difficult to maintain. To address these types of scenarios, we developed a hybrid filtering process which allows us to handle both

topological/combinatorial evolutions

and

probabilistic evolutions.

The filtering process maintains a minimal yet fully consistent

information state,

which can be thought of as a compact snapshot of all important events that

have happened in the system of interest. The efficient maintenance of the

information state is achieved through a careful

topological analysis of the space-time space

induced by the target-tracking task.

When it comes to decision making in a variety of civilian and security applications, for example search-and-rescue, pursuit-evasion, and monitoring, having the right information is of critical importance. These problems are known as

situational awareness (SA)

problems. As one can imagine, an effective cyber-physical system critically depends on its awareness of its ambient environment. A particularly important SA sub-category is target-tracking, in which (fixed and mobile) sensor observations are processed to provide the best possible estimate of one or more mobile targets. Because mobile targets will inevitably fall out of the

field-of-view (FOV)

of the sensors (see the figure on the left), consistent information can be difficult to maintain. To address these types of scenarios, we developed a hybrid filtering process which allows us to handle both

topological/combinatorial evolutions

and

probabilistic evolutions.

The filtering process maintains a minimal yet fully consistent

information state,

which can be thought of as a compact snapshot of all important events that

have happened in the system of interest. The efficient maintenance of the

information state is achieved through a careful

topological analysis of the space-time space

induced by the target-tracking task.

In the case where additional information of the targets is available,

we can also be more certain about their behavior. For example, if we have

the high-level specification of a robot or the story from a person, we may

compare the story (or specification) with the recordings from the sensors

to infer whether the story is consistent. For such cases, we

developed

dynamic programming based algorithms that allow the consistency check to

be performed in linear time. In a

follow-up work,

we further allow the verification to be approximate and can compute how

different the story/specification is from the sensor observation.

In the case where additional information of the targets is available,

we can also be more certain about their behavior. For example, if we have

the high-level specification of a robot or the story from a person, we may

compare the story (or specification) with the recordings from the sensors

to infer whether the story is consistent. For such cases, we

developed

dynamic programming based algorithms that allow the consistency check to

be performed in linear time. In a

follow-up work,

we further allow the verification to be approximate and can compute how

different the story/specification is from the sensor observation.

Topics

Shadow Information Spaces for Multi-Target Tracking

|

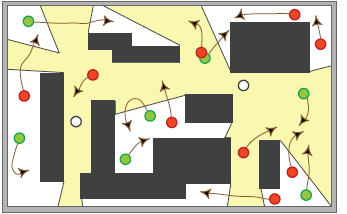

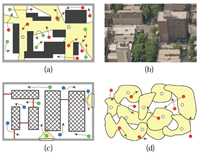

Imagine a game of hide-and-seek (variations include tag, tick, Cops and Robbers) is being played. After the hiders conceal themselves (subsequent relocations are allowed), the seekers, usually having a map of the environment, start to search for the hiders. Most people who played the game as school children know that an effective search usually begins with the seekers checking places having high probabilities of containing a hider, from previous experience: a closet, an attic, a tall bush, and so on. After the most likely areas are exhausted, the next strategy is then to carry out a systematic search of the environment, possibly with some seekers guarding certain escape routes. Occasionally, during game play, some hiders may attempt to relocate themselves to avoid being found. While they succeed sometimes, they may end up being spotted by the seekers and instead getting found earlier. Shadow Information Spaces research builds a model that abstracts the above hide-and-seek problem. We reason around the evolution of information that's hidden from the robots' sensors. This applies to a wide variety of real world problems, some of which are illustrated in the top figure on the left. Calling a connected component of the environment that is out of the robot's sensor field-of-view as a shadow, we argue that given the transitions of shadows, the problem of estimating those hidden information can be transformed into a maximum flow problem on a bipartitie graph structure in the nondeterministic case (bottom figure on the right). When the targets move probabilistically and sensors are not reliable, Bayesian filter are engaged to solve the problem. Since our approach mimics Bayesian filters but always begins with a combinatorial structure, we call it a combinatorial filter. |

The details are described in the following TOR paper:

Shadow Information Spaces: Combinatorial Filters for Tracking Targets. J. Yu and S. M.

LaValle. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 28(2), page(s): 440-456, Apr. 2012.

Verification with Cyber Detectives

|

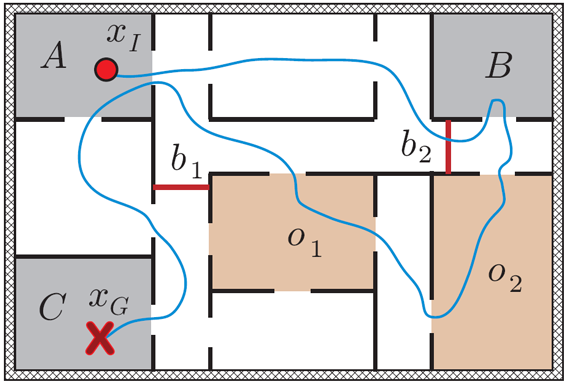

In computer science, robotics, and control, a frequently encountered problem is verifying that an autonomous system is performing as designed. For example, a service robot may plan a path to clean office rooms one by one. Due to internal or external factors, the robot may mistaken one room for another and fail to accomplish its task without knowing that it has failed. In such cases, it is desirable if external means could automatically determine that a robot has faltered. In this research, we introduce realistic abstractions of above problems and show that such formulations are computationally tractable. In this work, we provide fast, dynamic programming based algorithms for verifying the path taken by an autonomous system by observing samples of the system's trajectory. Our algorithm applies to multiple robots as well. |

Exact inference algorithm:

Cyber Detectives: Determining When Robots or People Misbehave. J. Yu and S. M.

LaValle. Algorithmic Foundations of Robotics IX, Springer Tracts in Advanced

Robotics (STAR), Springer Berlin/Heidelberg, vol 68, page(s): 391-407, 2011.

Approximate inference algorithm:

Story Validation and Approximate Path Inference with a Sparse Network of

Heterogeneous Sensors. J. Yu and S. M. LaValle. 2011 IEEE International Conference

on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2011).